It strikes me as ironic that while I struggle to find the right English word for my Japanese student, he can effortlessly retrieve it. Similarly, my 6-year-old daughter often finishes my sentences more eloquently than I can. At nearly 50 years old, I’ve started researching “menopause symptoms,” and I feel a fleeting sense of relief when I see memory issues listed. However, the shadow of Alzheimer’s disease looms ominously in the background.

My mother is battling dementia, likely due to Alzheimer’s, and so is everyone who cares for her. The vibrant matriarch we once knew is rapidly disappearing, replaced by a frail and bewildered figure who often repeats herself and experiences panic attacks, only to forget the comforting words we offer her moments later. Everyday terms are replaced with vague descriptions—cream cheese becomes “the white thing,” a colander is “the thing with holes,” and her cherished faith symbol is reduced to “the T-shaped object.”

Her grasp on time has become distorted; an event from just months ago now feels like it happened decades prior. While she can recall some family members, her recollection is inconsistent, leaving us uncertain if she has only forgotten their names or if she no longer remembers them entirely.

As my mother’s condition worsened, memories from my own adolescence resurfaced. My grandmother had lived with us after it was deemed unsafe for her to stay in her small Midwest apartment. At that time, I had no understanding of the profound sadness that accompanies the loss of one’s mental faculties.

To my 13-year-old self, Grandma’s repeated inappropriate comments and absurd questions seemed amusing (she was quite the character). I hadn’t known her before she came to live with us, so I couldn’t see the decline. I vividly recall the day my father, usually a man of few words, approached me before her arrival. “She forgets things,” he said, “and I don’t want anyone to make fun of her.” Those words struck a chord, revealing his deep love for his mother. In that moment, I began to see him as a vulnerable person, and my affection for him grew.

Initially, having Grandma in our home felt manageable. She was physically well, offered humor, and didn’t disrupt our routine. However, one night remains etched in my memory—a traumatic evening when she took a wrong turn in the dark hallway and fell down the stairs, fracturing her hip. This incident marked the beginning of the end for her time with us.

I remember accompanying my father to visit her in the hospital. He would come home from work and go straight to his suffering mother. While she begged to return home, promising to behave, he gently reiterated the reality of her situation, all while pulling his hair out in frustration as she insulted the nursing staff. His tenderness toward her was a lesson I absorbed deeply.

One day, I decided to visit Grandma alone after school. It was a significant step outside my comfort zone. As I sat with her, making awkward small talk, a nurse entered and asked, “Who do you have visiting you today, Gertrude?” Grandma responded that she didn’t know me, claiming she had never seen me before. I trudged home, feeling disheartened.

Now, these poignant memories resurface as I find myself in my father’s role. I observe the changes in my beloved mother. The slow loss feels agonizing, just as it did for my dad with his mother. It’s essential to treat those who once held power in our lives with the utmost kindness, especially as they become more fragile. My father’s message remains ingrained in my spirit.

Alzheimer’s runs in both sides of my family, having affected my mother and grandmother. It’s not unreasonable to fear inheriting this condition, especially when I occasionally struggle to recall a word, misplace an important item, or forget why I entered a room.

As it became clear that my mother could no longer live independently, my siblings and I had to discuss decisions regarding her care. During these conversations, I often replaced “Mom” with my own name. Will my path mirror hers? I can’t help but wonder how my four children will navigate similar discussions about me in the future. Which of them might shy away from confronting my decline? Who might want to help but not directly? Would any of them be willing to have me move in with them?

Sometimes my mother calls to ensure that I, along with my husband and children, are doing well. While she may not remember their names or ages, she knows they are family and feels the need to check on her “little chicks,” as she affectionately calls us. In those moments, I realize she is still present within her fading self.

I hold onto the hope that my own children will always be able to find me, even as I grapple with the uncertainty of the future.

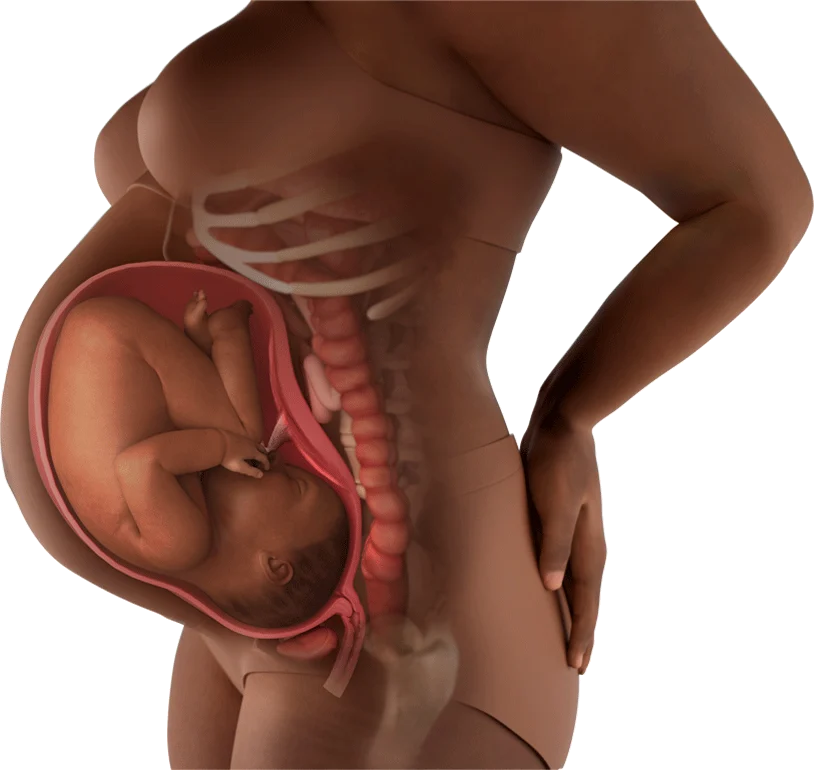

For further insight into issues surrounding fertility and home insemination, you can explore resources on pregnancy at Science Daily, or check out this handy home insemination kit. If you are looking to boost fertility, consider this fertility booster for men as well.

Summary

The emotional journey of caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s can be both heartbreaking and enlightening. As memory fades and the roles shift, the importance of compassion and understanding becomes paramount. The author reflects on personal experiences with family members affected by dementia, highlighting the challenges of facing the inevitable decline while still holding onto cherished memories.

Leave a Reply